Deep in the vast jungle of the internet, an elusive predator lies in wait: the WebRTC IP leak. This invisible hunter slithers through the dense digital undergrowth, silent and unseen, ready to strike its next target. The IP addresses of its unsuspecting victims are exposed in an instant. But its danger isn’t merely technical; if you’re a political activist in a repressive regime, leaking your IP could jeopardize your very life. Today, we embark on an expedition to track this hidden predator, uncover its secrets, and learn how to protect ourselves before it strikes.

Table of Contents

A Quick Disclaimer

Before we embark on this journey, here is a quick but important disclaimer: everything I share in this tutorial, including any code or techniques, is strictly for educational purposes. The goal is to help you understand and protect yourself against potential vulnerabilities like WebRTC IP leaks. Any misuse, abuse, or illegal application of the information provided here is entirely your responsibility. I do not condone or encourage any unethical or unlawful activity, and I am not liable for any consequences that may arise from such actions.

YouTube Tutorials

You can watch this tutorial on YouTube:

- The English video tutorial:

- The video tutorial in Persian:

What is WebRTC and What is it Used For?

WebRTC (Web Real-Time Communication) is a free, open-source technology that enables real-time communication between web browsers and mobile devices. By using WebRTC, developers can create seamless peer-to-peer (P2P) audio, video, and data connections without the need for additional plugins, custom software, or third-party extensions.

WebRTC simplifies the development of applications like video chats, screen sharing, and file transfers. It powers real-time communications directly within web pages using straightforward JavaScript APIs, making it a versatile tool for modern web and mobile applications.

Why Should You Care?

Even if you don’t actively use WebRTC, it might still impact you in ways that you might not be aware of. Most modern browsers or some HTML5-based mobile and desktop apps have WebRTC built-in, and it works silently in the background to enable things like video calls and file sharing.

WebRTC itself encrypts data and requires secure connections via HTTPS or localhost. But here’s the catch: even if you’ve taken steps to protect your privacy, such as using a VPN, WebRTC can expose your real IP address. This happens through a process called Interactive Connectivity Establishment (ICE), which allows peer-to-peer communication but can inadvertently leak both your public and local IPs (IPs in your own local network behind the NAT) to scripts running on a webpage.

In essence, a WebRTC leak can punch a hole in your VPN or firewall, effectively bypassing them, and exposing your real IP address to advertisers, hackers, and even malicious actors. This isn’t just about getting targeted ads—it’s a direct invasion of your privacy. Leaked IPs can allow malicious entities to track your online activity, correlate your actions across different sites, or launch targeted attacks on your network or device.

Even worse, if for example, you’re a journalist, activist, or anyone working in sensitive environments, your location or identity could be revealed to oppressive governments or bad actors. This could lead to serious consequences, including threats to your safety.

So, even if you don’t use WebRTC directly, it’s integrated into your browser and can expose you to risks you didn’t expect. By understanding these vulnerabilities, you can take proactive steps to protect yourself.

How Does WebRTC Leak Your IPs?

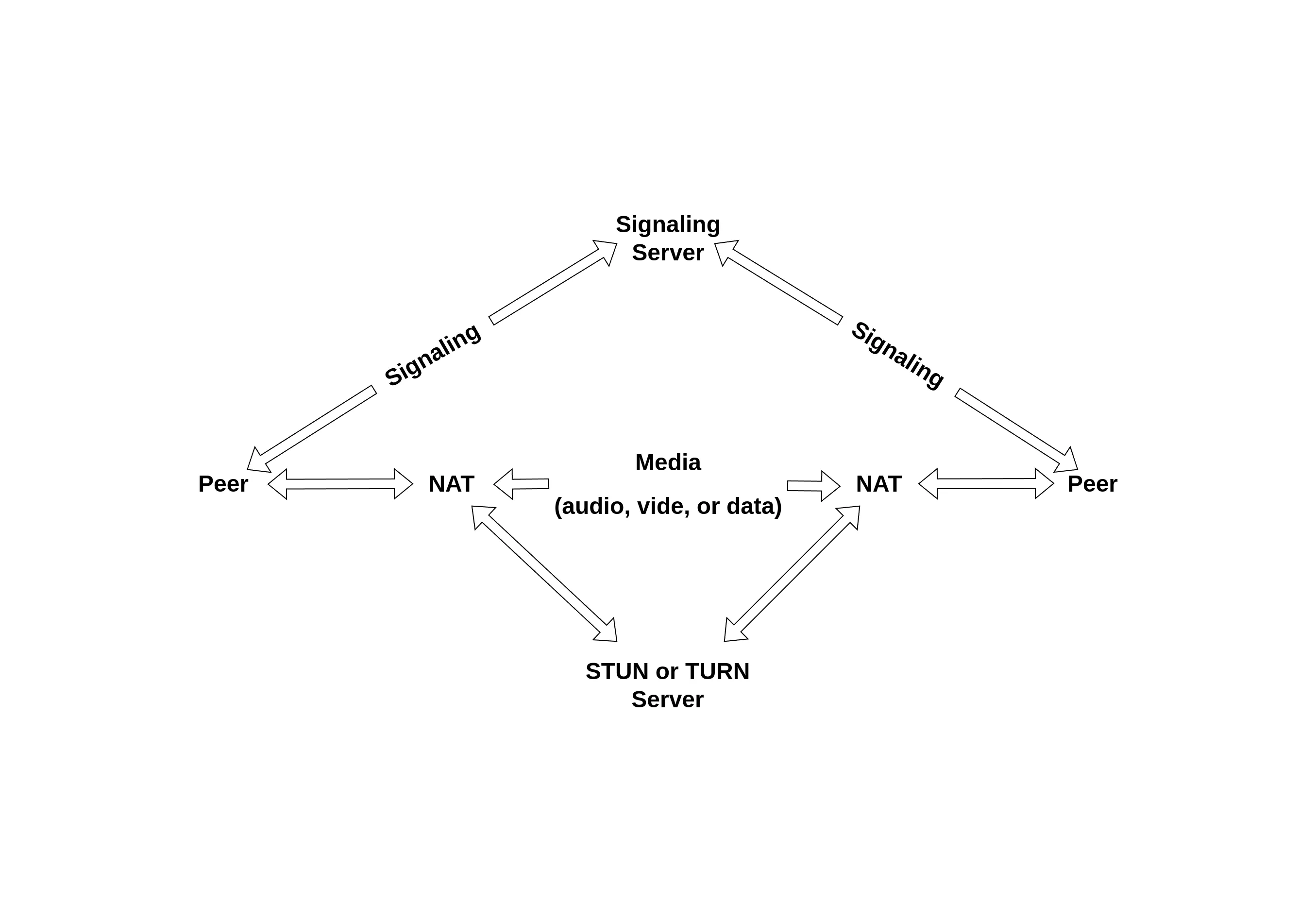

WebRTC establishes peer-to-peer (P2P) connections by enabling direct communication between two devices. To do this, the devices (or “peers”) must exchange connection details, such as their IP addresses, and agree on how to format the data they share (e.g., video resolution, codecs). Below is a simplified breakdown of how this process works and why it can lead to IP leaks:

To understand how the leak happens first let’s go over the key components of WebRTC:

-

Session Description Protocol (SDP): Peers exchange connection information (like IP addresses and media formats) using SDP. This exchange is called signaling and is required to set up a P2P connection. WebRTC doesn’t specify how signaling should be done. It could be via WebSockets, APIs, etc. It’s left to the developers to decide.

-

NAT and Public/Private IPs: Devices often sit behind NAT (Network Address Translation), which maps private IPs to a shared public IP for communication with the internet. This helps with security but can make direct P2P connections difficult.

-

STUN Servers: To establish a connection, a device uses a STUN server to discover its public IP and network configuration, which is included in the SDP and shared with the peer. Additionally, WebRTC queries the device’s local network interfaces to include private IP addresses in the ICE candidates during negotiation. While the STUN server only resolves public IPs, the private IPs are exposed locally by the WebRTC implementation.

-

TURN Servers (Optional): If NAT or firewall settings block direct peer-to-peer connections, a TURN server acts as a middleman, relaying data between peers. While this reduces the risk of direct IP exposure to peers, it’s less efficient than direct connections. Please note that as part of the WebRTC specification, private IPs would still get sent to the TURN server to create permissions for relayed communication. While this is intended functionality, it introduces a potential security risk if the TURN server is malicious or collaborates with a compromised website. Although such attacks can be expensive to execute—requiring control over TURN infrastructure and careful cooperation—they remain a viable risk for high-value targets.

-

ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment): ICE tries to find the best possible way for peers to connect by gathering connection methods (called ICE candidates) and testing them. ICE candidates often include both public and private IPs, which are shared with peers during the connection negotiation.

When a webpage uses WebRTC, it can trigger the ICE process, causing your browser to generate and share your IP addresses (both public and private) with the peer or server requesting them. In the same manner, malicious scripts running on a webpage can access ICE candidates and extract your IP addresses without your knowledge. Thus, even if you’re using a VPN, WebRTC can expose your real IP because the script queries your network interfaces directly, bypassing the VPN’s encrypted tunnel.

Some Intriguing Chrome Metrics

An exploration of the Chrome metrics historical data reveals fascinating insights into WebRTC’s usage patterns. Back in 2018, WebRTC accounted for approximately 8% of total Chrome page loads—likely translating to billions of loads per day. Notably, around 4% of total Chrome page loads (or half of all WebRTC-related page loads) involved calls to SetLocalDescription, a crucial step for initiating ICE candidate gathering.

In contrast, calls to SetRemoteDescription, essential for establishing an actual connection, were only observed in 0.04% of total page loads. This vast disparity suggests that 99 out of 100 peer connection requests stopped short of establishing an actual connection and were likely used for IP address gathering—an unintended and potentially malicious use of WebRTC’s capabilities that it was never originally designed for!

While WebRTC’s original design focused on enabling seamless peer-to-peer connections, this data highlights how its capabilities can be leveraged for purposes it was never explicitly intended for, such as harvesting user IPs for tracking, analytics, or exploitation.

mDNS: A Shield Against Local IP Leaks

While traditionally, WebRTC included local IP addresses (e.g., 192.168.x.x) in ICE candidates to facilitate peer-to-peer communication, fortunately, it’s not all doom and gloom. Browser vendors have spent years mitigating WebRTC IP leak vulnerabilities, and modern browsers have increasingly adopted mDNS (Multicast DNS) host candidates to the rescue—a feature designed to anonymize local IP addresses during the ICE process.

mDNS anonymizes local IP addresses during the ICE process by replacing them with randomized hostnames (e.g., random-uuid.local), effectively preventing direct exposure of your private IP to external entities such as websites or peers during WebRTC negotiation.

Please note that, despite enabling mDNS, your public IPv4, such as those provided by your ISP, or IPv6, which are globally routable, will still remain visible unless further mitigations (as we explain later) are in place.

While mDNS adoption and support varies, most major desktop browsers have implemented and enabled it by default. However, mobile browsers have lagged behind in adoption due to technical limitations. For instance:

-

Firefox and Chrome/Chromium rolled out mDNS on desktop a few years ago, with it being enabled by default to protect users (Firefox Bugzilla Report, Chromium Issue Tracker).

-

However, Firefox for Android and Chrome for Android have not implemented mDNS due to a lack of obfuscation support. It seems the underlying reason is due to Android’s multicast requirements, which involve a specific permission (

CHANGE_WIFI_MULTICAST_STATE). Additionally, according to the documentation using multicast can impact battery life, making it less suitable for mobile environments (Firefox Bugzilla Report, Chromium Issue Tracker).

To ensure your privacy is safeguarded, it’s always wise to test your browser for WebRTC leaks, as mDNS support and functionality may vary across different platforms and browser versions; so staying vigilant is key.

IPv6 Still an Issue

While mDNS has made strides in protecting local IPv4 addresses, as mentioned earlier, even with mDNS enabled, IPv6 leaks remain a significant privacy concern. When using a VPN, mDNS can protect your local IP from leaking, but your public IPv4 and IPv6 addresses may still be exposed unless additional protective measures are implemented.

While IPv4 generally offers more privacy by shielding internal devices behind NAT and a shared public IP address, IPv6 significantly weakens your privacy.

In short, IPv6 poses a significant concern when safeguarding your physical location is of utmost importance for several reasons:

Global Uniqueness:

-

IPv6 addresses are often globally unique, unlike private IPv4 addresses (e.g.,

192.168.x.x). -

This uniqueness means your IPv6 address can directly identify your device or network globally, potentially revealing your location or ISP.

Direct Accessibility:

-

Unlike IPv4, which often requires NAT to connect devices, IPv6 allows devices to be directly reachable from the internet.

-

This direct accessibility increases the risk of exploitation, especially with unpatched or vulnerable devices, as devices may be exposed to potential attacks without the protective barrier that NAT provides.

Tracking and Fingerprinting:

If someone obtains your IPv6 address, they could use it in correlation with other data to:

-

Link your activity across websites: The same IPv6 address appearing in multiple sessions can be used to track your online behavior.

-

Geolocate you: ISPs assign IPv6 blocks regionally, so your IPv6 address could reveal your approximate physical location.

-

Target you for attacks: If your device is directly accessible via IPv6, it could be vulnerable to hacking attempts or other network-based exploits.

Important Note: If a website collaborates with your ISP and has access to ISP logs, they can accurately identify you, regardless of the IP version. ISPs maintain logs that can link IP addresses to individual users, making it possible to trace online activity back to you.

Note: It’s possible to disable IPv6 altogether, forcing all traffic to use IPv4. This is the simplest option for those who do not require IPv6 connectivity.

Note: While your ISP assigns you a block of IPv6 addresses (known as a prefix, e.g., 2001:db8:1234::/64) to use within your network, and your operating system might utilize the IPv6 Privacy Extension (defined in RFC 4941) to protect against third-party tracking and address correlation, these measures are not effective at protecting you from ISP tracking or targeted identification, especially if an external entity collaborates with your ISP.

Hands-On Demonstration: Using Rust and JavaScript

Now, let’s get practical. To illustrate how easily WebRTC leaks can be exploited, I’ve developed a hypothetical demonstration using Rust and JavaScript. The complete source code is available on GitHub and GitLab.

In the videos above, I’ll walk you through deploying the demo to a VPS, showcasing its functionality step by step. The repository includes comprehensive documentation, making it straightforward to get it up and running on Microsoft Windows, various GNU/Linux distributions, or FreeBSD.

Stay tuned as we break down the mechanics and implications of WebRTC leaks!

Conclusion: Take Back Your Privacy

This demonstration highlights just how easily a WebRTC leak can compromise your privacy. The good news? Protecting yourself is straightforward:

-

Disable WebRTC: Use browser add-ons or settings to turn it off if you don’t need it. On Chrome/Chromium or any browsers based on Chromium, e.g. Brave, use an extension like WebRTC Leak Shield to prevent leaking any kind of IPs (local IPv4, public IPv4, and IPv6). And, on Firefox or any Firefox-based browsers, e.g. LibreWolf, navigate to

about:configin your address bar and setmedia.peerconnection.enabledtoFalse. Alternatively, on Firefox the WebRTC Leak Shield add-on can achieve the same results. Please note that in Incognito or Private Browsing modes by default extensions are disabled, so, it’s best practice to make sure these extensions are enabled even in Incognito or Private Browsing modes by checking the options Allow in Incognito in Chrome or Run in Private Windows in Firefox are enabled for the extension. For other browsers and platforms instructions exist all over the web. -

Ensure mDNS is Enabled: Modern browsers support mDNS to protect your local IP—double-check it’s enabled. On Chrome navigate to

chrome://flags#enable-webrtc-hide-local-ips-with-mdnsand Brave tobrave://flags#enable-webrtc-hide-local-ips-with-mdnsand ensure it’s enabled. On Firefox navigate toabout:configand ensuremedia.peerconnection.ice.no_host,media.peerconnection.ice.obfuscate_host_addresses, andmedia.peerconnection.ice.relay_onlyare all set toTrue. For other browsers and platforms instructions exist all over the web. -

Use a Reliable and Trusted VPN: Choose a VPN with WebRTC leak protection and a kill switch to safeguard your connection, even if the VPN connection drops, this feature is going to save you from leaking your IP!

-

Block Malicious Scripts: Install established privacy-focused add-ons to prevent malicious scripts from exploiting WebRTC vulnerabilities (e.g. uBlock Origin).

-

Test for WebRTC Leaks Regularly: Make it a habit to check your browser for leaks to ensure your protections are working.

Remember, this isn’t about fear—it’s about empowerment. By taking these simple steps, you can reclaim your privacy and stay safe in the digital jungle. Thanks for following this tutorial, and as always, stay secure out there!

See also

- Unreal Engine 5.7 Android Packaging & APK Build Tutorial | Meta Quest & HTC VIVE Standalone

- Optimizing Unreal Engine VR Projects for Higher Framerates (Meta Quest, HTC VIVE, FFR, ETFR, NVIDIA DLSS, AMD FSR, and Intel XeSS Tips Included!)

- Building Unreal Engine 5.6 From the GitHub Source Code on GNU/Linux With Android Support

- Rust Devs Think We’re Hopeless; Let’s Prove Them Wrong (with C++ Memory Leaks)!